01. Introduction

Lecturer: Clementine Gritti.

Course weighting:

- Quizzes: 20%

- 9 quizzes, 10 multi-choice questions with 4 options and 1 correct answer

- Assignment: 20%

- Released a week before the term break, due the week after

- Lab attendance: 10%

- If lab is missed, report can be emailed to course coordinator and TA by the following Friday

- Final Exam: 50%

CIA Triad:

- Loss of Confidentiality: when unauthorized people can access the data

- Loss of Integrity: when unauthorized changes can be made to the data

- Loss of Availability: when authorized users cannot access the data

02. Course Overview

What is Cyber security?

The NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) computer security handbook defines it as protections afforded to an information system to preserve confidentiality, integrity, availability (CIA) of system resources.

Terminology:

- Threat: potential security harm to an asset/system resource

- Attack: thread that is carried out. If successful, leads to undesirable violation of security

- Countermeasure: means taken to deal with attacks (prevention, detection, recovery)

- Vulnerabilities:

- Leaky: access to information given when it should not

- Corrupted: does the wrong thing or gives wrong answers

- Unavailable: impossible/impractical to access

Key questions:

- What assets need to be protected

- How are the assets threatened

- How can the threats be countered

Assets include:

- Hardware

- Software: OS, system utilities, applications

- Data: files, DB

- Networks: local/wide area network links, bridges, routers etc.

Types of Attacks

Passive:

- Does not alter information or resources in the system

- Hard to detect, easy to prevent

- Types of passive attacks:

- Eavesdropping/interception: attacker directly accesses sensitive data in transit

- Traffic analysis/inference: observations of the amount of traffic between the source and destination

Active:

- Alters information or system resources

- Hard to prevent, easy to detect

- Types of active attacks:

- Masquerade: attacker claims to be a different entity

- Message modification (falsification): message modified in transit

- DDoS (misappropriation): attacker prevents legitimate users from accessing resources

Inside:

- Initiated by entity inside the security perimeter

- Authorized to use the systems, but used in a malicious way

- Types of inside attacks:

- Exposure: sensitive data intentionally released to outsider

- Falsification: data altered or replaced

Outside:

- Initiated from outside the perimeter by an unauthorized or illegitimate user

- Types of outside attacks:

- Obstruction: communication links disabled, or communication control information altered

- Intrusion: attacker gains unauthorized access to sensitive data

Fundamental Requirements

Information security management requires:

- Threat identification

- Classification by likelihood and severity

- Security controls applied based on cost-benefit analysis

Countermeasures to threats and vulnerabilities:

- Computer security technical measures (access control, authentication etc.)

- Management measures (awareness, training)

What is Information Security?

ISO security architecture defines:

- Security: when vulnerabilities in assets/resources are minimized

- Asset: anything of value

- Vulnerability: any weakness that could be exploited to violate a system or its information

- Threat: potential security violation

Hence, information security is security where the assets/resources are information systems

Security Services and Mechanisms

OSI Security Architecture X.800: dated, but most definitions/terminology still relevant. Defines security threats, services, and mechanisms.

Security Services

A security service is processing/communication service that gives a specific kind of protection to system resources.

Security services include:

- Peer entity authentication: confirms entity is who they claim to be

- Data origin authentication: confirms origin of data unit/message

- Access control: protects against unauthorized use of resources

- Data confidentiality: protects data against unauthorized disclosure

- Traffic flow confidentiality: protects disclosure of data that can be derived from knowledge of traffic flow

- Data integrity: detects modification/reply of data in messages

- Non-repudiation: protects against the message creator falsely denying to creating the data

- Availability: protects against DDoS

- Encipherment: transforms data to hide its content

- Digital signature: mechanism to transform data using a signing key

From Stack Exchange:

- Non-repudiation: entity cannot deny to having sent/signed the message

- Message (or data origin) authentication: entity originally made the message

- Entity authentication: entity involved in current communication session

Security Mechanisms

A security mechanism is a method of implementing one or more security services.

Security mechanisms include:

- Data integrity: corruption-detection techniques

- Message Authentication Codes

- Authentication exchange: protocols to ensure identify of participants

- TLS

- Traffic padding: spurious traffic generated to protect against traffic analysis; usually used in combination with encipherment

- Control lists, passwords, tokens which indicate access rights

- Routing control: use of specific secure routes

- Notarization: use of trusted third party to assure source/receipt of data

03. Number Theory and Finite Fields

Discrete mathematics: cyroptology deals with finite objects (e.g. alphabets, blocks of characters)

Modular arithmetic; deals with finite number of values.

Basic Number Theory

Factorization

Given

An integer

Properties

If

If

Division algorithm

Given

Greatest Common Divisor

-

and - If

and , then -

Euclidean Algorithm

To find

Hence,

In psuedo-code:

def gcd(a, b):

r[-1] = a

r[0] = b

k = 0

while r[k] != 0:

q[k] = floor(r[k - 1]/r[k])

r[r + 1] = r[k - 1] - q[k]r[k]

k = k + 1

k = k - 1

return r[k]

Back-Substitution

Find

Can be rewritten as:

Example:

Back-substitution:

The result shows that

Modular Arithmetic

Given

In other words,

Residue Class

The set

The set

Groups

A group

- Closure:

for any and all - Identity: there is an element

such that for any and all - Inverse: there is an element

such that for any and all - Associativity:

for any and all

A group is abelian when it is the operation is commutative;

Cyclic Groups

The order

The order

A group is cyclic if it has a generator.

Computing Inverses Modulo

The inverse if

Theorem: let

The Euclidean algorithm can be used to find the inverse of

If

Hence, starting from

Group of Primes Modulus

Properties:

-

-

is cyclic -

has many generators (in general)

It can be thought of as the multiplicative group of integers

Finding Generators

A generator of

Lagrange theorem: the order of any element must exactly divide

To find a generator of

- Compute all distinct prime factors

of -

is a generator iff for all

Example

Find a generator for

-

: not a generator as -

: and so is a generator

Groups of Composite Modulus

For any non-prime

Properties:

-

is a group -

is not cyclic in general - Finding its order is difficult

e.g.

Example

Find a generator for

-

: not a generator as -

: -

-

-

-

-

-

- Hence, the order of

is equal to , cycling through all elements in the group before repeating - NB: every element is guaranteed to be in

as it is a group and hence has closure over the multiplication operation

-

Fields

A field

-

is an abelian group under the operation with the identity element -

is an abelian group under the operation with identity element - Distributivity:

for

Theorem: only finite fields of size

Finite Field

For a finite field

- Multiplication and addition are done modulo

- Its multiplicative group is exactly

Finite Field

- Addition modulo

: XOR ( ) - Multiplicative group:

Finite Field

Arithmetic in this field is considered as polynomial arithmetic where the field elements are polynomials with binary coefficients. e.g.

Properties:

- Polynomial division can be done easily using shift registers

- Adding two strings: add their coefficients modulo

(XOR) - Multiplication with respect to a generator polynomial

- AES uses

- AES uses

- Multiplying two strings: multiply them as polynomials, then take remainder of division by

03. Classical Encryption

Terminology

- Cryptography: the study of designing systems

- Cryptoanalysis: the study of breaking systems

- Steganography; the study of concealing information; not covered in this course

Cryptography transforms data based on a secret called the key. It provides confidentiality and authentication:

- Confidentiality: key needed to read the message

- Authentication: key needed to write the message

Cryptosystems:

- A set of plaintexts holding the original message

- A set of ciphertexts holding the encrypted message

- Sometimes called cryptogram

- A set of keys

- A function called the encryption or encipherment which transforms the plaintext into a ciphertext

- An inverse function called the decryption or decipherment which transforms the ciphertext into the plaintext

Symmetric key cipher (secret key cipher):

- Encryption/decryption keys known only to the sender/receiver

- Secure channel required for transmission of keys

Asymmetric key cipher (public key cipher):

- Each participant has a public and private key

- Can be used to both encrypt messages and create digital signatures

Notation for Symmetric Encryption Algorithms

- Encryption function

- Decryption function

- Message/plaintext

- Cryptogram/ciphertext

- Shared secret key

Encryption:

Decryption:

Methods of Cryptanalysis

What resources are available to the adversary? Computational capabilities, inputs/outputs to the systems, etc.

What is the adversary aiming to achieve? Retrieving the whole secret key? Distinguishing between two messages?

Exhaustive Key Search

Adversary tries all possible keys. Impossible to prevent such attacks; can only ensure there are enough keys to make exhaustive search too difficult computationally.

Note that the adversary may find the key without exhaustive search or even break the cryptosystem without finding the key.

Preventing exhaustive key search is a minimum standard.

Attack Classification

Ciphertext only attack: the attacker has access only to intercepted ciphertexts.

A cryptosystem is highly insecure if it can be practically attacked using only intercepted ciphertexts.

Known plaintext attack: the attacker knows a small amount of plaintexts and their corresponding ciphertexts.

Chosen plaintext attack: the attacker can obtain the ciphertext from some plaintext it has selected (attacker has ‘inside encryptor’).

Chosen ciphertext attack: the attacker can obtain the plaintext from some ciphertext it has selected (attacker has ‘inside decryptor’).

A cryptosystem should be secure against chosen plaintext and ciphertext attacks.

Kerckhoff’s Principle

Kerckoff’s Principle states the that the attacker has complete knowledge of the cipher; the decryption key is the only item unknown to the attacker.

Secret, non-standard algorithms are often flawed, providing mainly security through obscurity.

Alphabets

Historical ciphers: define alphabet for the plaintext and ciphertext

Roman alphabet:

- Sometimes it includes spaces, upper/lowercase characters, punctuation

- Sometimes maps the alphabet to numbers:

Statistical attacks depend on using the redundancy of the alphabet:

- Distribution of single letters, digrams, trigrams are used

- Exact statistics vary by sample

Basic Cipher Operations

Transposition: characters in plaintext are mixed up with each other (permutations)

Substitution: each character is replaced by a different character

Transposition Cipher

Permuting characters in a fixed period

The plaintext is seen as a matrix with

Key is

There are

Cryptanalysis

Frequency distribution of ciphertext and plaintext characters are the same.

If

Knowledge of plaintext language digram/trigrams can help to optimize trials.

Simple Substitution Ciphers

Each character in plaintext alphabet replaced by character in ciphertext alphabet using a substitution table.

This is called a monoaphabetic substitution cipher.

Caesar cipher:

-

th letter of the alphabet mapped to the th letter using the key - Encryption:

- Decryption:

- Guess

by finding the most frequent character in the ciphertext and mapping it to the most frequent character in the language (e.g. (space), ‘e’)

Random simple substitution cipher:

- Each character assigned to a random character of the alphabet

- Encryption/decryption done using substitution table

- If the alphabet has

characters, there are keys - One-to-one mapping, so second character can only be assigned to

characters

- One-to-one mapping, so second character can only be assigned to

- Caesar cipher is a special case of the random simple substitution cipher

- Frequency analysis: use the most frequent characters, common di/trigrams such as ‘the’

Polyalphabetic Substitution

Multiple mappings from plaintext to ciphertext: smoothens frequency distribution.

Typically periodic substitution ciphers based on a period

Given

A plaintext message:

it is encrypted to:

If

Key generation:

- Select block length

- Generate

random simple substitution ciphers

Encryption: encrypt the

Decryption: use the same substitution table as encryption.

Vigenère Cipher

Based on shifted alphabets.

The key

Let

e.g. if

Cryptanalysis

Identifying period length:

- Kasiski method

- Cryptool uses autocorrelation to automatically estimate period

Once period identified, the

Autocorrelation

Given ciphertext

English is non-random; there is better correlation between two texts with the same shift size.

Find peaks in the value of

Kasiski Method

If you identify sequences of characters that occur multiple times, find the distance between them; the period is likely to be a multiple of the period.

If you find multiple sequences with different distances, the period is likely to be a common divisor.

Once the period is found, the separate alphabets can be attacked separately; at this point, it is just a Caesar cipher.

Other Ciphers (for use by hand)

Beaufort cipher: like Vigenère, but

Autokey: starts off as the Vigenère cipher, but the plaintext defines the subsequent alphabet. Hence, the cipher is not periodic.

Running key cipher: practically infinite set of alphabets generated from a shared key. This is ofen an extract from a book called the book cipher.

Rotor Machines

Enigma: each character encrypted with a different alphabet with a period of ~17,000; would never repeat in the same message (in practice).

Hill Cipher

Polygram/polygraphic cipher: simple substitution of an extended alphabet consisting of multiple characters.

Has linearity, making known plaintext attacks easy.

Given

Encryption: multiplying the

Decryption: multiplying the matrix

Example

Each plaintext pair written as column vector. If there are insufficient letters, they are filled with uncommon letters (e.g.

Plaintext:

Encryption:

Decryption:

Cryptanalysis

Known plaintext attacks possible given

-

-

-

, so

Then

Comments:

- The plaintext message

may not be invertible - Ciphertext-only attacks follow known plaintext attacks with the extra task of finding probable blocks of matching plaintext-ciphertext

- e.g. if

, the frequency distribution of non-overlapping pairs of ciphertext characters can be compared with the distribution of pairs of plaintext characters

- e.g. if

- Cryptool defaults to an alphabet of

(where is space)

05. Block Ciphers

Main bulk encryption algorithms used in commercial applications. AES is one example of such algorithm.

Principles

Block ciphers are symmetric key ciphers where each block of plaintext encrypted with the same key.

A block is a set of plaintext symbols of a fixed size, typically 64 to 256 bits in modern ciphers.

They are used in configurations called modes of operation.

Notation

-

: plaintext block of length bits -

: ciphertext block of length bits -

: key of length bits - Encryption:

- Decryption:

Criteria

Shannon defined two encryption techniques:

- Confusion: substitution used to make the relationship between

and as complex as possible. - Diffusion: transformations used to dissipate the statistical properties of

across .

Repeated use of techniques can be used using the concept of a product cipher.

Product & Iterated Ciphers

Product Cipher

Cryptosystem where encryption performed by applying/composing several sub-encryption algorithms: output of one block used as input to next block.

Often composed of simple functions

Iterated Cipher

Special product ciphers called iterated ciphers where:

- Encryption divided into

similar rounds - Sub-encryption functions are the same function

: the round function - Each round key/subkey

is derived from the master key using a process called key schedule

Encryption

Given plaintext block

Decryption

There must be an inverse function

Types of Iterated Ciphers

Substitution-Permutation Network (SPN) e.g. Advanced Encryption Standard (AES).

Feistel Cipher e.g. Data Encryption Standard (DES).

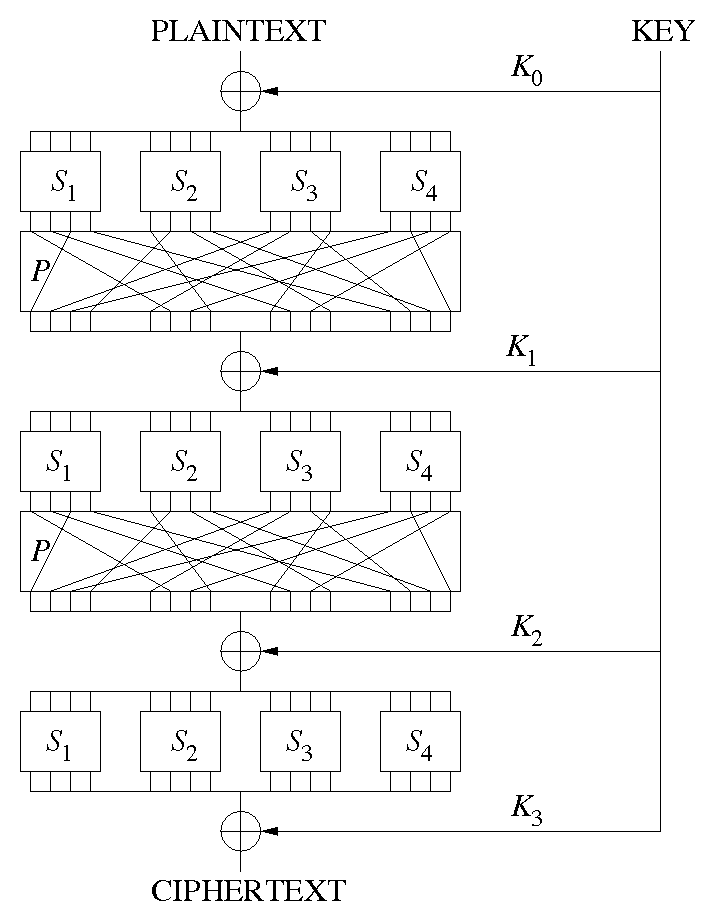

Substitution-Permutation Network

Block length

Substitution

i.e. mapping some binary number of size

Permutation

i.e. swapping the order of bits in the entire block around.

Operation

- Round key

XORed with current state block : - Each sub-block substituted applying

- The whole block permuted using

Example

- 4 round keys

- 4 S-boxes

- 1 P-box

- Last round does have a P-block

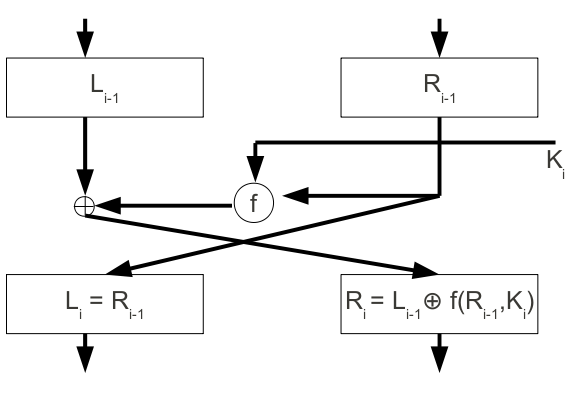

Feistel Cipher

Round function swaps the two halves of the block to form a new right hand half.

Encryption

Plaintext block

For each round:

The output is the ciphertext block

Decryption

Split

For each round:

The choice of

Differential and Linear Cryptanalysis

Differential cryptanalysis: chosen plaintext attack using correlation in the differences between two input plaintexts and their corresponding ciphertexts.

Liner cryptanalysis: known plaintext attack that theoretically break DES.

Modern block ciphers normally immune to both attacks.

Avalanche Effects

Key avalanche: a small change in key (with the same plaintext) should result in a large change in ciphertext.

Plaintext avalanche: a small change in plaintext should result in a large change in ciphertext: changing one bit should change all bits in the ciphertext with a probability of

Key avalanche is related to Shannon’s notion of confusion, plaintext avalanche to Shannon’s notion of diffusion.

DES

Designed by IBM researchers, became US standard in 1976. 16-round Feistel cipher with key length of 56 bits and data block length of 64 bits.

The key length is actually 64 bits, but the last bit of every byte is redundant.

Encryption

- All bits of

permuted using an initial fixed permutation of - 16 rounds of Feistel operations applied, denoted by function

- Each round uses a different 48-bit subkey

- The subkey is defined by a series of permutations and shifts

- A final fixed inverse permutation

is applied

The 64-bit ciphertext block

Decryption requires only reversing the order in which the subkeys are applied.

Feistel Operation

- 32 bits expanded to 48 bits using a padding scheme which repeats some bits

- XOR the 48 bits with the 48-bit subkey

- Break 48 bits into 8 blocks of 6 bits

- Each block

transformed using substitution table , resulting in blocks of length and hence a total of 32 bits. - A transformation table is used to determine the output value

- If the input block is

, the row number is given by and the column number by

- A permutation is applied to the result

Brute Force Attacks

Testing all the possible

The key can be identified by using a small number of ciphertext blocks and looking for low entropy in the decrypted plaintext.

Double Encryption

Let

Encryption:

If both keys have length

Meet-in-the-Middle Attack

Let

- For each key

, store in memory - For any key

, check if (i.e. matches any ciphertext stored in memory) - If this is found,

is and is - Check if key values work for other

pairs

- If this is found,

Requirements:

- Storing one plaintext block for every key:

64-bit blocks - An encryption operation for every key

- A decryption operation for every key

Expensive but still much cheaper than brute-forcing

Triple Encryption

Requires three keys:

This increases the computational requirements enough to make it secure against MITM attacks.

NIST SP 800-131A (2015) approves two-key triple DES, where

OpenSSL removed triple DES in 2016. Office 365 stopped using triple DES in 2018.

AES

Designed in an open competition after controversy over DES. Winning submission is ‘Rijndael’.

- 128-bit data block

- 128-, 192- or 256-bit master key

- Byte-based design

- Substitution-permutation network

- Initial round key addition

- 10, 12, or 14 rounds (depending on key size)

- Final round

Algorithm

State Matrix

16-byte data block size arranged in a

Mixture of finite field operations in

Round Transformation

Each round has four basic operations:

- ByteSub (non-linear substitution): substitute each byte wth a different value using a substitution table

- ShiftRow (permutation): rotate first row right by zero bytes, second row right by one byte… (bytes wrap to left)

- MixColumn (diffusion): each column is replaced with result of it being multiplied by a matrix

- AddRoundKey: XORs array with round key

Substitution-permutation network with block length of

S-box uses look-up table.

Key Schedule

Master key is 128/192/256 bits.

Each of the 10/12/14 rounds uses a 128-bit subkey. There is one subkey per round plus one initial subkey, all derived from the master key.

Security

Some weaknesses but no significant break; most serious real attacks can reduce effective key size by around two bits.

Vulnerable to related-key attack: attacker obtains a ciphertext encrypted with a key related to an actual key in a specified way.

Comparisons with DES

- Data block size: 64 vs 128 bits

- Key size: 56 vs 128/192/256 bits

- Design:

- Both iterated ciphers

- DES uses Feistel; AES uses SPN

- AES substantially faster in both hardware and software

06. Block Cipher Modes of Operation

Block ciphers encrypt single blocks of data, but many applications require multiple blocks to be encrypted sequentially and breaking the plaintext into blocks and encrypting them separately can be insecure.

Modes of operation are standardized with different security and efficiency characteristics.

NIST has many standards (e.g. SP 800-38 series) for this.

Important Features of Different Modes

Different modes can provide confidentiality, authentication (and integrity) or both.

Modes for confidentiality normally include randomization.

Different modes have different efficiency and communication properties.

Randomized Encryption

Problem: the same plaintext block is encrypted to the same ciphertext block every time - allows patterns to be found in long ciphertexts.

Prevention: randomizing encryption schemes by using an initialization vector (IV) which propagates through the entire ciphertext. It may need to be either random or unique.

Alternatively, there could be a variable state which is updated with each block.

Efficiency

Parallel processing: encrypting/decrypting multiple plaintext/ciphertext blocks in parallel.

Error propagation: a bit error in the ciphertext which results in multiple bit errors in the plaintext after decryption.

Padding

Requiring the plaintext to consist of complete blocks.

NIST suggested padding method: append a single

Notation

- Plaintext message

of length blocks -

-th plaintext block for - Ciphertext message

-

-th ciphertext block for - Key

- Initialization vector

Modes can be applied to any block cipher.

Confidentiality Modes

Electronic Code Book (ECB) Mode

A basic mode of a block cipher; each block is encrypted with a key, IV is not used.

Encryption

Decryption

Properties

| Randomized | Padding | IV | Parallel encryption | Parallel decryption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Required | None | Yes | Yes |

Error propagation: within blocks.

Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) Mode

Blocks chained together: the plaintext XORed with previous ciphertext (or IV for the first block) and then encrypted.

Encryption

for

Decryption

Where

Properties

| Randomized | Padding | IV | Parallel encryption | Parallel decryption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Required | Random | No | Yes |

Error propagation: within blocks and into specific bits in the next block.

Parallel decryption means that decryption does not require the plaintext of previous block. However, it does require the ciphertext of the previous block.

Commonly used for bulk encryption, was often used in TLS up to TLS 1.2.

Counter (CTR) Mode

Synchronous stream cipher mode.

Encryption

The counter and a nonce (IV) are initialized using a random value

That is,

Then, this result is encrypted with the key

Finally, it is XORed with the plaintext block

Decryption

Properties

| Randomized | Padding | IV | Parallel encryption | Parallel decryption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Optional | Unique | Yes | Yes |

A one-bit change in ciphertext produces one-bit change in the plaintext at the same location.

This allows access to specific plaintext blocks without decrypting the whole stream.

CTR mode is the basis for authenticated encryption in TLS 1.2.

Authentication Mode

Message Integrity

Ensuring messages are not altered in transmission: preventing an adversary from re-ordering, replacing, replication and deleting message blocks to alter the received message.

Message integrity and authentication are treated as the same thing.

Proving message integrity is independent from using encryption for confidentiality.

Message Authentication Code (MAC)

Where

The output

Given both parties share the key

- The sender computes

- The message

and tag are sent - The receiver computes

on the received message and checks that

MAC Properties

Only the sender and receiver can produce

If

It has the basic security property of unforgeability: it is infeasible to produce

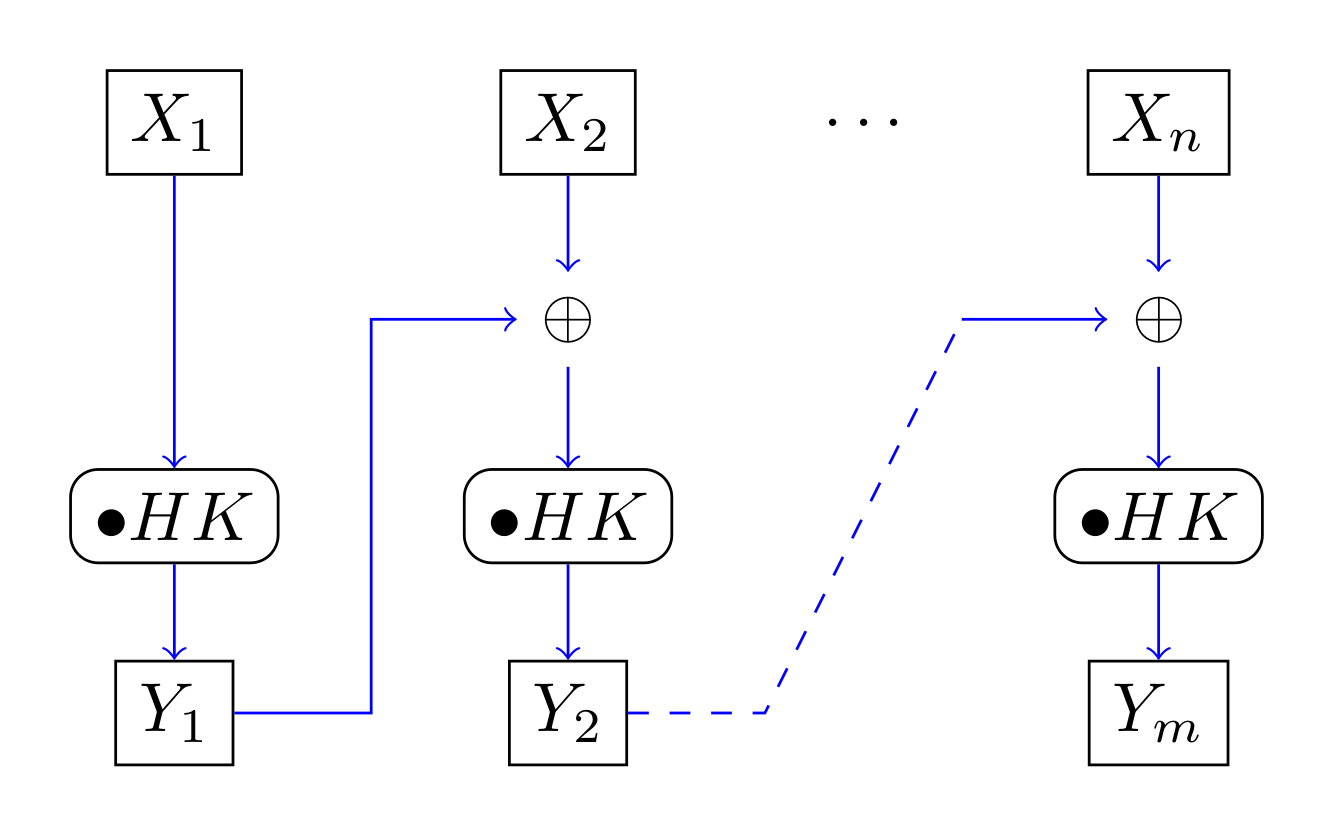

Basic CBC-MAC

Using block cipher to create a MAC providing message integrity (but not confidentiality).

If

For

It is unforgeable as long as the message length is fixed.

- If the IV is random, the IV needs to be sent along with the MAC

-

- Hence, the attacker can modify

and together such that XORing them gives the same result. As is not modified, none of the subsequent ciphertexts (and hence the tag) stays unchanged

Cipher-based MAC (CMAC)

Standardized, NIST version of CBC-MAC. The IV is all zeroes. The below is as per RFC4493.

Two keys

For

For the final block:

(That is, 1 and then enough zeros to fill up a block)

Then do the same operation as with the previous blocks , except that

Finally,

NIST allows the length of the tag,

The standard recommends the MAC tag

-

is a limit on how many invalid messages are detected before is changed -

is the acceptable probability that a false message is accepted

Authenticated Encrypted Mode

Two types of input data:

- Payload: both encrypted and authenticated

- Associated data: only authenticated

NIST specifies two modes:

- NIST SP-800-38C (2004) for Counter with CBC-MAC

- NIST SP-800-38D (2007) for Galois/Counter (GCM)

Both use CTR mode but add integrity in different ways.

Both are used in TLS 1.2 and 1.3.

Counter with CBC-MAC (CCM) Mode

CBC-MAC for authentication of all data, CTR mode encryption for the payload.

Inputs:

- Nonce

for CTR mode - Payload

of bits - Associated data

Compute the CBC-MAC tag, getting

Split the message

Then, use CTR mode to compute blocks.

From RFC3610:

- Authentication using CBC-MAC:

-

Blocks

generated. contains the metadata such as the nonce, payload length etc. Later blocks contain the payload and associated data.

-

- Encryption using CTR mode:

- Generate a keystream

where is the block number. - Output message

. starts with , not - Output authentication value

- Generate a keystream

- Decryption requires key

, nonce , authenticated data and ciphertext - Authenticated data must be sent separately!

CCM Mode Format

Lengths of

If

e.g. TLS 1.2:

07. Pseudorandom Numbers and Stream Ciphers

Random Numbers

Randomness: want any specific string of bits is exactly as random as any other string.

True random number generator (TRNG): physical process which outputs each valid string independently with equal probability.

Pseudorandom number generator (PRNG): deterministic algorithm which approximates a TRNG.

For practically, TRNGs are often used to provide a seed for a PRNG.

Pseudorandom Number Generator (PRNG)/Deterministic Random Bit Generator (DRBG)

Entropy source includes:

- Physical noise source

- Digitization process

- Post-processing stages

Periodic health tests required to ensure reliable operation.

Each generator takes a seed as an input, outputting a bit string before updating its state.

The seed should be updated after some number of calls.

DRBGs expose some functions:

- Instantiate: set the initial state using a seed

- Generate: provide bit string for each request

- Reseed: input new random seed and update the state

- Test: check correct operation

- Uninstantiate: delete/zeroising the state

The DDRBG should prevent an attacker from being able to reliably distinguish between its output and a truly random string. There are two types of resistance:

- Backtracking resistance: attacker with access to current state of DRBG should not be able to distinguish between the output of earlier calls and random strings

- Forward prediction resistance: attacker with access to current state of DRBG should not be able to distinguish between output of later calls and random strings

CTR_DRBG

Block cipher in counter (CTR) mode - AES with 128-bit keys recommended.

DRBG initialized with seed whose length is equal to key length PLUS block length.

Seed defines a key

CTR run iteratively with no plaintext.

Update Function

Each request to the DRBG generates up to

State

Up to

Dual_EC_DRBG

Older standard based on elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem and with many flaws.

Much slower than other DRBGs.

Secret deal between NSA and RSA Security to use this as the default PRNG in their software was reported in 2013.

Stream Ciphers

Generates keystream using a short key and initialization vector

Each element of the keystream is used to successively encrypt one or more ciphertext characters.

Stream ciphers are usually symmetric.

Synchronous Stream Ciphers

Keystream is generated independently of the plaintext; both the sender and receiver need to generate the same keystream and be synchronized.

Keystream and plaintext are XORed together, so receiver simply needs to XOR the ciphertext with the keystream to decrypt.

Vigenère cipher can be seen as a periodic synchronous stream cipher where each shift is defined by a key letter.

CTR mode of operation for a block cipher can be used to generate a keystream.

Binary Synchronous Stream Ciphers

For each time interval

-

is the binary keystream -

is the binary plaintext -

is the binary ciphertext

Encryption:

Decryption:

One-Time Pad

Key is random sequence of characters such that each is independently generated.

Each character in the key is only used once; this provides perfect secrecy.

Alphabet can be of any length but is usually either binary or a natural language alphabet.

Perfect Secrecy

Shannon’s definition:

-

Message set

-

Ciphertext set

-

; probability that is encrypted given that is observed - In most cases, messages

are not equally likely; that is, given a ciphertext, some messages are more likely than others

- In most cases, messages

-

For all messages

and ciphertexts :

The ciphertext should be independent of the plaintext

One-Time Pad Perfect Secrecy

Let a ciphertext

The probability that

As each keystream is chosen with equal probability,

Any keystream is possible and so given any plaintext, every possible ciphertext is generated with equal probability.

Vernam Binary One-Time Pad

- Plaintext : binary sequence

- Ciphertext: binary sequence

- Keystream : binary sequence

- Must be same length as the plaintext

- Encryption:

- Decryption:

Properties

Shannon showed that any ciphertext with perfect secrecy must have as many keys as there are messages. Hence, one-time pad is the only unbreakable cipher.

However, this requires secure communication between fixed parties and secure key generation, transportation, synchronization, and destruction which are all difficult due to the size of the keys.

Visual Cryptography

Encryption splits an image into two shares, each pixel being shared in a random way (similar to splitting a bit in a one-time pad).

Each share alone reveals no information about the image, but the two images can be overlayed to reveal the plaintext.

Prominent Stream Ciphers

A5 Cipher

Binary synchronous stream cipher applied in most GSM communications. Three variants:

- A5/1 is the original algorithm defined in 1987

- A5/2 is the weakened version intended for deployment outside Europe

- A5/3 (KASUMI) used in 3G systems

A5/1 Design

Three linear feedback shift registers (LFSRs) whose outputs are combined.

The LFSRs are irregularly clocked, making the overall output non-linear.

It has a 64-bit keystream such that 10 bits are fixed to zero; hence, the effective key length is 54 bits.

RC4 Cipher

Ron’s code #4 . Originally owned by RSA but leaked in 1994. Too weak to use in real systems nowadays, but was was widely deployed in TLS before 2013.

ChaCha Algorithm

Possible replacement of RC4 designed in 2008.

Faster than AES; as few as 4 cycles/byte on x84 processors.

Number Theory for Public Key Cryptography

- Number theory problems used in public key cryptography

- Need efficient ways of generating large prime numbers

- Definitions of hard computational problems are the base of crypto systems

Chinese Remainder Theorem (CRT)

Let

Let

Given integers

Where:

Condensed Equation:

Example

Find

-

and -

and are relatively prime so CRT can be used -

For

Make sure you replace

For

Example 2

Find

Hence

Where:

-

- As

,

- As

-

- As

,

- As

Hence:

Test:

-

as required -

as required

Euler Function

Given the positive integer

e.g.

Properties

if

e.g. for

Fermat’s Theorem

Let

Euler’s Theorem

More general case of Fermat’s theorem.

If

Primality Tests

Testing for primality by trial division not practical for large numbers.

There are many probabilistic methods, although these may fail in exceptional circumstances.

Agrawal, Saxena, Kayal 2002: polynomial time deterministic primality test, although still impractical.

Fermat Primality Test

Fermat’s little theorem: if

If

The probability of failure can be reduced by repeating the test with different base values of

Given the number

- Pick

at random such that - If

, return as being composite. Otherwise, return probable prime - The powers can be reduced using the following properties:

-

- The powers can be reduced using the following properties:

Some composite numbers such as

Example

Check if

Using

Hence it is composite, so we do not need to make further checks.

Miller-Rabin Test

Most widely used test for generating large prime numbers. It is guaranteed to detect composite numbers of the test is run sufficiently many times.

Modular square root of

There are four square roots of

- Two are

and - Two are called non-trivial square roots of

If

Miller-Rabin Algorithm

Let

- Pick

at random such that - Set

- If

, return probable prime - For

to : - If

, return probable prime - Else, set

- If

- Return composite

If the test returns probable prime,

If

As the algorithm is run

In practice, the error probability is smaller: when

Why The Miller-Rabin Test Works

Given a random

Hence,

Each number on the sequence is the square of the previous number (modulo

If

- Either

OR - There is a square root of

somewhere in the sequence whose value is (which is equal to

If a non-trivial square root of

Example

Let

- Choose

-

-

so: -

-

-

-

- Hence,

will never occur - Hence,

must be composite

-

NB:

Example 2

Let

Let

-

- This is not

so: - Repeat up to

times: -

Hence,

Generation of Large Primes

- Choose a random odd integer

of the same number of bits as the required prime - Test if

is divisible by any of a small list of primes - If not:

- Apply the Miller-Rabin test five random or fixed based values of

- If

fails any test, set and return to step 2

- Apply the Miller-Rabin test five random or fixed based values of

This incremental method does not produce completely random primes. If this is an issue start from step 1 if

Basic Complexity Theory

Two aspects:

- Algorithmic complexity: how long does it to take to run a particular algorithm

- Problem complexity: how long does it to take to run the best known algorithm for the given problem

Express this complexity using ‘big O’ notation; in terms of the space and time required to solve the problem for a given size.

Hard Problems

Integer factorization: given an integer of

Discrete logarithm problem (base 2): given a prime

There are no known polynomial algorithms to solve the problems; the best known algorithms are sub-exponential.

Factorization Problem

Trial by division: exponential time algorithm

Some fast methods exist, although they only apply to integers with particular properties.

Bets known general method: number field sieve, a sub-exponential algorithm.

As

Discrete Logarithm Problem

Given a prime

Given

, find such that .

(i.e. find the power given the remainder)

This can be written as

If

Example

Find

Hence

Example 2

Find the discrete logarithm of the number

i.e. solve

There is a cycle with powers of

09. Hash Functions and MACs

Hash Functions

A public function

-

is simple and fast to compute -

takes as input message of arbitrary length and outputs a message digest of fixed length

Security Properties

- Collision resistant: it should be infeasible to find any two values

and such that - Second-preimage resistant: given a value

, it should be infeasible to find a different value such that - Preimage resistant (one-way): given a value

, it should be infeasible to find any input such that

If an attacker can break second-preimage resistance, they can also break collision resistance.

Birthday Paradox

If there is a group of 23 people, there is over a 50% chance that at least two people have the same birthday.

If choosing

Hence, if

Today,

In comparison, to get a 50% change of guessing the key of a block cipher requires only

Iterated Hash Functions

Iterated hash functions splits the input into fixed-size blocks and operates on them sequentially.

Merkle-Damgård Construction

A compression function

The compression function takes two

m = m_1 || m_2 || m_3 || … || m_l

m_1 m_2 m_3 m_l pad+len

| | | | |

| | | | |

v v v v v

IV ---> h ---> h ---> h --...-> h---> h ---> H(m)

Security: if the compression function

Weaknesses:

- Length extension attacks: if padding appended but not message length, there is no difference in the output of the message and the message with the right padding added. Hence, if the message is

, they can extend this to , where is the additional contents added by the attacker. Since the hash is the full internal state of the hash function, the attacker can use the hash and continue calulating the rest of the hash for , allowing them to create valid hashes without knowledge of or the rest of the message. Adding message length stops this attack - Second-preimage attacks: not as hard as they should be

- Collisions for multiple messages: not that too much more difficult than finding collisions for two messages

The Merkle-Damgård construction is used in MD5, SHA-1 and SHA-2.

Standardized Hash Functions

MDx Family

Proposed by Ron Rivest, widely used in the 1990s.

128-bit output, all broken.

Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA)

Based on MDx family, more complex design with 160 bit output.

SHA-0 introduced 1993, SHA-1 in 1995 with minor changes. Both broken.

SHA-2 Family

Standardized 2015.

Hash sizes of 224, 256, 384 or 512 bits.

Minimum recommended is SHA-256 (256 bit hash, 512 bit blocks) - same security as AES-128.

Most secure is SHA-512: 512 bit hash, 1024 bit blocks.

Padding:

- Message length field: 64 bits for 512 bit blocks, 128 bits for 1024 bit blocks.

- Always at least one bit of padding

- There is one

1bit, some number of0bits (enough to make blocks full) and then the length field - Padding and length fields may add an extra block

SHA-3

MDx, SHA families based on the same basic design which were vulnerable to a few unexpected attacks.

Keccak function picked by NIST in 2015 as as SHA-3: uses sponge function instead of compression.

Using Hash Functions

Hash functions do not depend a key; anyone can calculate it so it is not encryption.

However, it does help to provide data authentication:

- Authenticating the hash of a message to authenticate the message

- Building blocks for MACs

- Building blocks for signatures

Password storage:

- Pick random salt: makes it resistant to rainbow table attacks as there needs to be a different dictionary for every salt

- Compute

- Store salt and hash value

Message Authentication Code

Ensures message integrity. takes in a message

The tag

Unforgeability: not feasible to produce a valid pair

Unforgeability under chosen message attack: even with access to an oracle that can calculate the MAC for an input message of the attacker’s choosing, they cannot create a valid tag themselves (i.e. guess the private key from tags they ask the oracle to generate).

MAC from Hash Function (HMAC)

Proposed by Bellare, Canetti and Krawczyk in 1996.

Can be built from any iterated hash function

With a key

opad = 0x5c5c...5cipad = 0x3636...36

HMAC is secure if

HMAC is often used as a pseudorandom function to derive subkeys.

Authenticated Encryption

A and B share a key

Two options:

- Split

into and , encrypting with and using with a MAC - Use an authenticated encryption algorithm that provides both

Combining Encryption and MAC

Three options:

- Encrypt-and-MAC: encrypt

, apply MAC to and send the ciphertext and tag - Encryption algorithms usually have an IV but MACs usually don’t; if the same message is sent multiple times the MAC will be the same

- MAC-then-encrypt: calculate the MAC on

, encrypt then send the ciphertext - Encrypt-then-MAC: encrypt

, calculate the MAC on the ciphertext and then send and tag

Encrypt-then-MAC is the safest option:

MAC-then-encrypt was used in older versions of TLS while newer versions use authentication encryption modes.

https://crypto.stackexchange.com/questions/202/should-we-mac-then-encrypt-or-encrypt-then-mac

CTR Mode for Block Ciphers

Synchronous stream cipher. Counter initialized with random nonce

where

Encryption and decryption is simply XORing the plain/ciphertext with

Galois Counter Mode (GCM)

CCM mode cannot be used for processing of streaming data: formatting function for

Combines CTR mode on the block cipher

- Input: plaintext

, authenticated data , nonce - Outputs: ciphertext

, tag - Lengths

and are 64 bit values -

and are the minimum numbers of zeros required to expand and to complete blocks

-

- Length

of is 128 bits, is 96 bits long - Initial block input:

- Function

increments 32 MSB of the input string by

GHASH:

Output is

Decryption:

- Receiver receives ciphertext

, nonce , tag , authenticated data - Receiver computes tag

using shared key , compares with - If the same,

can be computed by generated the same keystream from CTR mode

10. Public Key Cryptography

Public key cryptography (PKC) has some features that symmetric key cryptography (SKC) does not and is applied for key management in protocols such as TLS and IPsec.

Discrete log-based ciphers are alternatives to PKC.

One-Way Functions

A function is one-way if

It is not known if one-way functions exist, but there are many functions that are believed to be one-way:

- Multiplication of large primes: the inverse function is integer factorization

- Exponentiation: the inverse function takes discrete logarithms

Trapdoor One-Way Functions

A function such that

Example: let

- The inverse function will be to find

such that - From Euler’s theorem,

for any integer , assuming co-prime to - Hence,

( and are co-prime to each other) -

for some integer - That is,

- Hence,

-

- Integer factorization is assumed to be a hard problem; hence

cannot be computed easily - Hence, only someone with knowledge of

’s factors, the trapdoor, can find the inverse function

Asymmetric Cryptography

Another word to describe public key cryptography.

Public key cryptosystems, such as the Diffie-Hellman key exchange, are designed by using a trapdoor one-way function: the trapdoor is the decryption key.

This allows a public key to be stored in a public directory: anyone can obtain the public key and use it to form an encrypted message that only a person with the private key can decrypt.

Asymmetry: encryption and decryption keys are different. Encryption key is public and known to anybody; the decryption key is private and known only to its owner.

Finding the private key from the public key must be a hard computational problem.

Advantages of shared key/symmetric cryptography:

- Key management is simplified: they dot not need to be transported confidentially

- Digital signatures can be obtained

RSA

Designed in 1977 by Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman from MIT (patent expired 2000).

It is based on integer factorization problem.

Algorithm

Key generation:

- Randomly choose two distinct primes,

and from the set of all primes of a certain size - Compute

- Randomly choose

such that - Compute

- Set the public key

- Set the private key

Encryption:

- Input is value

such that - Compute

Decryption:

- Compute

Any message must be pre-processed:

- Coding it as a number

- Adding randomness (to avoid repeating ciphertext for the same plaintext)

Numerical Example

Key generation:

- Let

, -

-

- Let

-

(Solve using the Euclidean algorithm)

-

Encryption:

- Let

-

Decryption:

Numerical Example 2

Key generation:

- Let

, -

-

- Let

-

Find

-

Solve

using the Euclidean algorithm:

-

Encryption:

- Let

-

Decryption:

Correctness

Decrypting an encrypted message: does

As

Hence,

Now we must show that

Case 1: Coprime to n

Case 2: Multiple of p or q

Since

Supposing that

Applying Fermat’s theorem,

As

- There is a unique solution

to: -

-

- Hence,

-

- And

is satisfied too

Applications

- Message encryption

- Digital signature

- Distribution of key for symmetric key encryption (hybrid encryption)

- User authentication

Implementation

A few implementation details

Key Generation

Generating large primes

- At least 1024 bits recommended for today

- Simple algorithm: select random odd number

of required length, check if prime, incrementing by two if not

Choice of

- Choose at random for best security

- But small values are often used in practice: more efficient

-

is smallest possible value; very fast but has security issues -

is a popular choice -

should be at least to prevent known attacks such as Wiener’s attack

Encryption/decryption

Fast Exponentiation

A square-and-multiply modular exponentiation algorithm.

In binary,

If

Code:

// 2^66 % 100

M = 2 // base

n = 100 // modulus

e = [0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1] // exponent as bits, LSB first

z = 1; // Result - M^e \bmod n

for(let i = 0; i < e.length - 1; i++) {

if(e[i] == 1) {

z = (z * M) % n;

// z = 1 initially so first multiplication is unnecessary

// Hence e.filter(i => i == 1).length - 1 multiplications

}

M = (M * M) % n; // equals base^{2^{i + 1}}

// When i = 0, M = base^1 - right for the next iteration

// Does not need to be calculated for the i + 1 == e.length

// as the value is used for the next iteration

}

Cost:

- If

the algorithm uses squarings - If

bits of are high, there are multiplications (first computation has , but is initially one) -

is 2048 bits so is at most 2048 bits. Hence, computing requires at most 2048 modular squarings or multiplications - On average, only half of

’s bits are high so there are only 1024 multiplications

Faster Decryption Using CRT

Decrypting

Compute

Solve

Hence,

Then we can output

Speedup

Exponents

Hence, computing each of

Hence, storing

Padding

Encryption directly on the message encoded as a number is bad as it is vulnerable to attacks:

- Building up a dictionary of known plaintexts

- Guessing the plaintext and checking if it encrypts to the ciphertext

- Håstad’s attack

Hence, a padding mechanism must be used to prepare the message for encryption, adding redundancy and randomness.

Håstad’s Attack

The same message

Equations can be solved using the CRT to obtain

Padding Types

- PKCS 1: simple ad-hoc design

- Optimal asymmetric encryption padding (OAEP):

- Bellaware and Rogaway, 1994

- Security proof in a suitable model

- Standardized in IEEE P1363

Security

Attacks

Mostly avoided through the use of standardized padding mechanisms.

Possible attacks:

- Factorization of the modulus

: this is believed to be a hard problem, so should be fine as long as is large enough. - Finding

from and : as hard as factorizing (Miller’s theorem) - Quantum computers: Shor’s theorem can theoretically factorize

in polynomial time - Timing analysis: using timing of decryption process to obtain information about

- Demonstrated in practice in smart cards

- Avoided by randomizing the decryption processes

Practical Problems with Key Generation

- OpenSSL implementation in some systems would use massively-reduced randomness (2008)

- Lenstra in 2012 analyzed 6 million RSA keys:

- Found 4% of keys were identical

- Found 0.2% of keys provided no security as they shared one prime factor with each other

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

Two users sharing a secret using only public communication.

Public elements:

- Large prime

- Generator

Alice and Bob randomly select values

Over an insecure channel, Alice sends

Both compute the secret key

Example

Let

- Alice sends

- Bob sends

Both compute

Properties

Security

Relies on the difficulty of the discrete logarithm problem.

If an attacker intercepts

There is no better known way for a passive adversary to find the shared secret.

Authenticated Diffie-Hellman

In the basic protocol, messages are not authenticated: a man-in-the-middle-attack is possible where the attacker acts as a proxy between the two parties, decrypting messages from one party and then re-encrypting messages to send to the other party with the other key.

- Alice chooses

, sending and - Bob chooses

, sending , and - Alice sends

- Both computes

Both parties must know each other’s public signature verification keys,

Static and Ephemeral Diffie-Hellman

The above protocol uses ephemeral keys: keys are used once. In the static protocol:

- Alice chooses a long-term private key

and public key - Bob chooses a long-term private key

and public key - Alice and Bob find a shared secret

which is static -

stays the same until either party changes their public key

-

Elgamal Cryptosystem

Proposed by Elgamal in 1985, turning the Diffie-Hellman protocol into a cryptosystem for encryption and for signature.

Alice combines her ephemeral private key with Bob’s long-term public key

Algorithms

Key generation:

- Select prime

, generator - Select long-term private key

- Compute

- Set the long-term public key

Encryption:

- Select a message

- Choose at random an ephemeral private key

- Compute

and - Compute the ciphertext:

-

Decryption:

- Compute

-

Correctness

- Alice knows ephemeral private key

- Bob knows long-term private key

- Both compute the Diffie-Hellman value for the two public keys:

-

- Diffie-Hellman value

used as the mask for the message

Example

Key generation:

- Prime

- Generator

- Long-term private key

- Compute

- Bob’s public key is

Encryption:

-

Alice wants to send

-

chosen at random -

Computes

Decryption:

-

Bob computes

-

Bob recovers

Security

- Dependent on the difficulty of the discrete logarithm problem: if broken, they could determine the private key

from - Many users could share the same

and - Padding not required: ephemeral key

randomizes the ciphertext

Elliptic Curves

Algebraic structures formed from cubic equations.

Curves are defined over any field.

e.g. set of all

A point on the curve is the identity element, and by defining a binary operation on the points (e.g. multiplication), we can form a group over elliptic curve’s points: the elliptic curve group.

Any elliptic curve can be used but most applications use standardized curves generated in a verifiably random way (e.g. NIST curve P-192 has curve of

Discrete log defined on elliptic curve groups: if elliptic curve operation operation denoted as multiplication, definition is the same as in

Elliptic curve implementations require smaller keys compared to RSA:

| Symmetric key | RSA modulus | EC element length |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | 1024 | 160 |

| 128 | 3072 | 256 |

| 192 | 7680 | 384 |

| 256 | 15360 | 512 |

From Ars:

- Symmetric across horizontal axis

- Any non-vertical line intersects with the curve at most three times. Group operation:

- Infinity,

, is the identity element - Draw line intersecting the two points

- If the points are the same, use the tangent

- Find the third point intersecting the line

- If the points are the same and it is at an inflection point, use the same point

- Find the opposite point

- Infinity,

11. Digital Signatures

MACs allow entities with shared secrets to generate valid tags, providing data integrity and authentication.

Digital signatures use public key cryptography to provide additional properties: only the owner of a private signing key can generate a valid signature.

Non-repudiation: the signer cannot deny they have signed a message.

Properties

Algorithms: Key & signature generation, signature verification.

Key generation algorithm outputs a private signing key,

Signature generation:

Signature verification:

Correctness: if

Unforgeability: computationally infeasible to generate signature for any message without key. Note that the signing algorithm may be randomized - many possible signatures for a message.

Stronger security definition: forging a new signature should be difficult even if they can obtain signatures for messages of their choice (chosen message oracle).

Security Goals

Key recovery: recovering the private signing key

Selective forgery: choosing a message and obtaining a signature for that message.

Existential forgery: forging a signature on any message not previously signed (even a meaningless message).

Modern digital signatures should be able to resist existential forgery under a chosen message attack.

RSA Signatures

Key Generation

Key generation is the same as for encryption keys:

- Public verification key:

, where is the product of two large primes and - Private signing key:

, , such that

A fixed public parameter, the hash function

Signature Generation and Verification

Given message

Given claimed signature

Discrete Logarithm Signatures

Three versions:

- Original Elgamal signatures in

(1985) - Digital signature algorithm (DSA) standardized by NIST

- DSA based on elliptic curve groups: ECDSA

Elgamal Elements in

-

is a large prime -

is a generator of -

is the private signing key, where -

is part of the public key - A message

in

Signature generation:

-

Pick random

such that -

Compute

-

Solve

for : -

Output the tuple

Signature verification: check if

Correctness

Fermat’s Little Theorem

Fermat’s little theorem: given a prime

if

Proving Correctness

Let

Hence, coming back to the Elgamal signature verification equation (and noting that

as required.

Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA)

Published by NIST in 1994. Based on Elgamal signatures but calculations are simpler and signatures shorter: done in a subgroup of

Prime

Generator

where

Let

Both sides of the equation are reduced modulo

Key generation:

- Choose secret key

- Compute the public key,

.

Signature generation:

- Message

- Pick

- Compute

- Why

?

- Why

- Compute

- Set the signature as

Signature verification:

- Check if

, - Compute

- Compute

- Compute

- Check that

Verification equation is the same as with Elgamal except that all exponents and the final result is reduced modulo

Correctness

Fermat’s Little Theorem

Where

Hence

Proving Correctness

Let

Hence, coming back to the Elgamal signature verification equation (and noting that

as required.

Elliptic Curve DSA (ECDSA)

Similar to DSA except that:

-

becomes the order of the elliptic curve group - Multiplication modulo

is replaced by the elliptic curve group operation - After operations on group elements, only the

coordinate is kept from the pair

Compared to DSA, public keys are shorter but signatures are not (326 to 1142 bits).

12. Public Key Infrastructure and Certificates

Public Key Infrastructure (PKI)

NIST: “… key management environment for public key information of a public key cryptographic system”

Must consider:

- Key lifecycle: generation, distribution, storage and destruction

- Trusted legal/business entities:

- Registration Authorities (RAs): vouch for the identify of a user

- Validation Authorities (VAs): verify identities

- Certification Authorities (CAs): issue digital certificates (certifying public key TODO?)

Digital Certificates

How do you confirm the relationship between the public key and the claimed owner of that key? Through the use of digital certificates:

- Contain public key and owner identity

- Metadata such as signature algorithm, validity period

Certificates are signed by a certification authority (that should be trusted by the certificate verifier).

Certification Authority

A CA creates, issues and revokes certificates for subscribers and other CAs.

A CA has a certification practice statement (CPS) which covers processes such as checks before issuing certificates, physical/procedural security controls, revocation processes.

X.509 Certificate

Now RFC 5280, currently on version 3.

Important fields:

- Version number

- Serial number

- Signature algorithm identifier

- Issuer name (CA name)

- Subject name (user to which the certificate is issued)

- Public key information

- Validity period

- Digital signature (generated by CA)

Verification:

- Check CA signature is valid

- Requires user to have public key of the CA

- Check any conditions set in the certificate (e.g. validity period) are correct

Certification paths: CAs can issue certificates to other CAs. Hence, as long as there is a chain of CAs leading to a trusted root CA, the last CA can be trusted and hence the certificate can be validated.

Phishing: attacker can make URL and interface similar to a genuine site

Extended validation certificates: certificate issued by only some CAs after they have validated the entity’s legal identity. Different icon in browsers, but mostly ignored by users.

Revocation:

- Certificate marked as invalid even if its validity period is current

- User must check which certificates have been revoked

- Certificate Revocation List (CRL): each CA issues list of revoked certificates that must be downloaded by clients

- Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP): server responds to requests about specific certificates

Public Key Pinning:

- Depreciated feature that allowed websites to tell browsers to fix the public key used to verify certificates

- If CA was compromised, attacker can issue another certificate for the website but the browser would continue to use the pinned key for some time period

PKI Examples

Hierarchical PKI:

R Root

/ \

/ Y Intermediate

A \ CAs

Z

/ \

B C Users

CA certifies public key of entity below. If non-hierarchical, certification can be done between any CAs.

Browser PKI:

- Multiple hierarchies with preloaded public keys as root CAs

- Intermediate CAs can be added

- Users can add their own certificates

- Most servers send their public key and certificate through TLS

OpenPGP PKI:

- Used in PGP emails

- Certificate includes ID, public key, validity period, self-signature

- NO certification authorities

- Various key servers store public keys

- Web of trust: users can attest to association between public key and username

13. Key Establishment

Distribution of cryptographic keys to protect subsequent sessions. In TLS, public keys allow clients/servers to share a new communication key.

Kerberos: key establishment without public keys.

Key Management

Key management has four phases:

- Key generation: keys should be generated such that they are all equally likely to occur

- Key distribution: keys should be distributed in a secure fashion

- Key protection: keys should be accessible only to authorized parties

- Key destruction: once a key has performed its function, it should be destroyed such that it (TODO the encrypted data?) has value to an attacker

Hierarchy

Keys often organized into a hierarchy. In a two-level hierarchy, there are long- and short-term keys:

- Long-term/static keys are used to protect the distribution of session keys. They may last anywhere from a few hours to a few years, depending on the application

- Short-term/session/ephemeral keys are used to protect communications in a session. They may last anywhere from a few seconds to a few hours, depending on the application

Key Establishment

Symmetric keys with ciphers (e.g. AES, MAC) are used in practice for session keys as as they are more efficient than public key algorithms.

Long-term keys can be symmetric or asymmetric.

Key Distribution Security Goals

Authentication: they should be able to authenticate that the receiver is the party they intended to send the key to.

Confidentiality: no adversary can obtain the session key accepted by a particular party.

In formal models, the protocol is broken if the adversary can distinguish the session key from a random string.

Mutual and Unilateral Authentication

Mutual authentication: both parties achieve the authentication goal.

Unilateral authentication: only one party achieves the authentication goal. This is done by most real-world key establishment protocols: typically clients authenticate the server with client authentication happening later.

Adversary Capabilities

A strong adversary knows the details of the cryptographic algorithms and can:

- Eavesdrop on all messages

- Alter messages sent

- Re-route messages to any other party

- Obtain the session key used in any previous run

Distribution of Pre-Shared Keys

A trusted authority (TA) generates and distributes long-term keys to all users when they join the system. Their involvement ends here in the pre-distribution phase so if there are no new users they can go offline.

A simple scheme is to assign a secret key for each pair of users, but this will not scale well as the number of keys grows quadratically.

Probabilistic schemes reduce key material at each party by forwarding messages to other parties that hopefully have a link to the final receiver. Hence, it offers only a high probability of a secure channel between any two parties and requires other nodes to be trusted as they must decrypt and re-encrypt the message. This is suitable for sensor networks.

Key Distribution using Symmetric Keys

Key distribution with online server.

A TA shares a long-term shared key with each user. They distribute session keys to users when requested and hence, the TA is highly trusted and is a single point of attack. Scalability may also be a problem.

Needham-Schroeder Protocol

Widely-known key establishment protocol published 1978. Found vulnerable to replay attacks in 1981 - attacker can replay old messages that a honest party will accept an old session key.

Notation:

- Two parties,

and - TA

-

and share a long-term key -

and share a long-term key - New session key

generated by - Nonce

, randomly generated by and respectively for one-time use -

: sends message to -

: message encrypted using key . There is assumed to be some authentication mechanism

Protocol:

Replay Attacks

If an attacker

To defend against this, the established key must be fresh for each session:

- Random challenges (nonces)

- Timestamps

- Counters

The repaired protocol uses random challenges. After

Tickets can also be used: if

Kerberos

Now on V5, released 1995. Standardized as RFC 4120. Used in Windows as the default domain authentication method.

Kerberos allows:

- Secure network authentication service in an insecure network

- Single sign-on: users only need to enter their username/password once per session

- Access to different online services using individual tickets

- Session keys to be established in an authenticated and confidential fashion

It is a 3-level protocol:

Level 1

Client

Where:

-

is the symmetric key shared between and , usually generated on login from -

is the symmetric key generated by -

is the nonce generated by to ensure is fresh -

is the long-term key shared between and -

is valid for some validity period .

At the end of this exchange,

Level 2

Client

Where:

-

is a session key shared between and -

is a long-term key shared between and -

is a nonce -

is a ticket for service with validity period -

where is a timestamp - The ticket-granting server must check that the timestamp is valid

The ticket-granting server must also check that the client has permission to access the service

In practice, the AS and TGS are the same machine.

Level 3

Client

Where:

The reply from

Limitations

Realms (domains over which an authentication server has authority to authenticate a user) must share keys with every other realm, so although multiple realms are supported it has limited scalability.

Key Distribution using Asymmetric Cryptography

No online TA is required. Instead, public keys (managed by PKI - certificates and CAs) is used for authentication. Users are trusted to generate good session keys (so hopefully each party has a good PRNG).

Key transport: user chooses key material and sends it to another party (encrypted, possibly signed). Does NOT provide forward secrecy.

Key agreement: Diffie-Hellman or some other protocol where both parties provide input to the key. The messages are signed, providing authentication. Provides forwards secrecy.

TLS supports both key transport and agreement.

Forward Secrecy

If a long-term key is compromised, the attacker can now claim to be the owner of the key. If key transport is used, all previous session keys will be compromised.

A protocol provides (perfect) forwards secrecy if compromise of the long-term secret keys do not reveal session keys previously agreed using the long-term keys.

Signed Diffie-Hellman

Computations done in

- Generator

- Random values

and chosen by each party where -

is a signature on message from signed with their signing/long-term key -

is a signature on message from signed with their signing/long-term key -

and are and ’s identities respectively - Both parties know each other’s public verification key

- Long-term signing keys provide only authentication, hence it has perfect forward secrecy

Protocol:

-

sends , -

sends , and -

checks signature. If valid, computes session key

-

- A sends

-

checks signature. If valid, computes session key

-

14. Transport Layer Security Protocol

The most widely used security protocol.

History:

- SSL 2.0 developed by Netscape in 1994, 3.0 in 1995

- Standardized as RFC 2246 in 1999, called TLS 1.0

- TLS 1.1 (4346) in 2006, fix issues with non-random IVs, weaknesses from padding

- (the below are good to use)

- TLS 1.2 (5246) in 2008 allows standard authenticated encryption

- TLS 1.3 (8446) in 2018 had major changes and separated key agreement and authentication algorithms

Overview

Three higher-level protocols:

- TLS handshake protocol

- TLS alert protocol signals events

- TLS change cipher spec protocol for changing cryptographic algorithm (not available in TLS 1.3)

TLS record protocol provides basic services to the higher-level protocols. Stack:

|----------------------------------------|

| TLS | TLS change | TLS | HTTP/ |

| Handshake | cipher | alert | Other |

|----------------------------------------|

| TLS record protocol |

|----------------------------------------|

| TCP |

|----------------------------------------|

| IP |

|----------------------------------------|

TLS Record Protocol

TLS offers:

- Message confidentiality - message contents cannot be read in transit

- Message integrity - receiver can detect modifications made to the message in transit

These services may be provided by a symmetric encryption algorithm (confidentiality) and MAC (authentication/integrity). TLS 1.2 and above offer authenticated encryption modes (CCM, GCM), combining these two services into one.

The handshake protocol establishes the symmetric session keys used by the record protocol.

The record protocol also deals with dividing messages into blocks and re-assembling received blocks and possibly with compressing/decompressing block contents.

Format

HEADER

|--------------------------------------|

| Content | Major | Minor | Length |

| type | version | version | |

|--------------------------------------|

ENCRYPTED CONTENTS

|--------------------------------------|

| Plaintext |

| (possibly compressed) |

| (not available in TLS 1.3) |

|--------------------------------------|

| MAC |

| (unless authentication encryption) |

|--------------------------------------|

Content type can be change-cipher-spec, alert, handshake or application-data.

TLS 1.3 does not allow the cipher suite to be changed to prevent downgrade attacks - a new session must be created.

Major version is 3 for TLS and minor version 1 to 4 for TLS 1.0 to 1.3.

Length of data is in octets.

Operation

- Each application-layer message is

bytes or less - Compression removed in TLS 1.3 after attacks discovered, null by default in TLS 1.2

- Authenticated data: data, header and implicit record sequence number

- Plaintext: data and MAC (unless using authenticated encryption)

- Session keys: established in handshake protocol

- One key for each of MAC and encryption for each direction

- A single key if using authenticated encryption

- Specification: encryption/MAC algorithms specified in negotiated cipher suite

MAC algorithm:

- SHA-2 allowed in TLS 1.2 and above

- MD5 and SHA-1 not supported in TLS 1.3

Encryption algorithm:

- Block cipher in CBC or a stream cipher